Corporatized Water Management in the Volcan River’s Basin

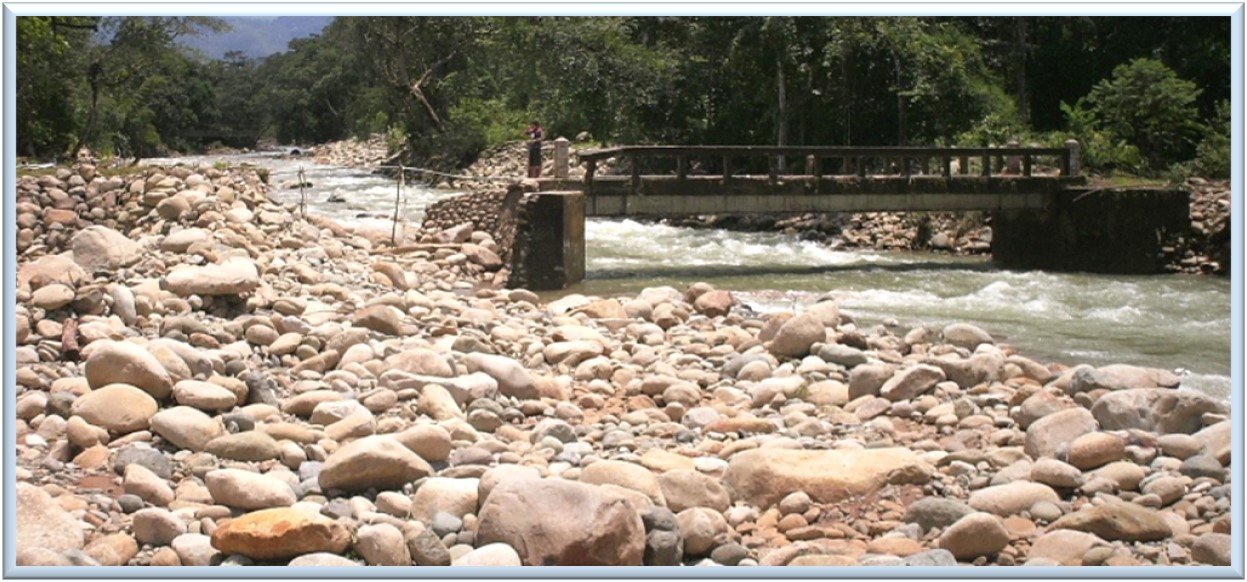

Volcán de Buenos Aires, Costa Rica

Fresh Del Monte Produce, Inc., one of the world’s leading producers of fresh pineapple, and the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ) recently signed an agreement that places the company in a position to lead efforts to protect two damaged basins in Costa Rica and one in Guatemala. This alliance, marketed as a new model for water management, is in keeping with global initiatives to promote corporate leadership in water, in part to assure investors that companies have enough water for their products as the climate changes.1 This represents a profound shift, beyond assuring the market that Del Monte’s areas of production are sustainable, to promising to protect rivers in the larger basins where the company operates.

In one of the pilot sites for this project, located in the south of Costa Rica, the GIZ-Del Monte alliance isn’t placing at center of its efforts the necessary scientific, legal, and economic frameworks (environmental flows; Rights of Nature; post-growth) that would enable society to meaningfully question the viability and tradeoffs of the current economic system, based on pineapple, cattle, and sugar cane. How secure is this economy, in a time of rapid climate change? Should there be instead a significant and rapid shift away from the current export, growth model, to small-scale farming, as difficult as this shift would be? The GIZ-Del Monte alliance focuses on regenerating and reforesting the upper part of the basin where the company operates—originally deforested by ranchers before Del Monte’s arrival in the region in 1979. While this is a positive step in and of itself, the reason behind, and narrative supporting it, aren’t: The current economy, primarily pineapple, needs more water, given that the rivers where it has its concessions are deteriorating.

Before the GIZ-Del Monte alliance, but in ways even more since it’s taken shape, it’s been difficult for civil society, government agencies and NGOs to raise questions about the fact that the company—the largest holder of water concessions in Costa Rica—has 98% of concessioned water in the basin where it is located. What are the environmental, social, and economic tradeoffs of these concessions? It has been and remains very difficult to discuss this question. Nor is it possible to openly discuss the fact that downstream from company operations (and from cattle ranches and sugar cane plantations), the Térraba-Sierpe Wetland, a Ramsar site, is being destroyed, in part, by sedimentation and agrochemicals generated in the upper basin. In the wake of the destruction, certain families that have fished for generations are abandoning their work and turning to the international drug trafficking cartels; others are falling into deeper levels of poverty. 2

These arguments, reflecting the ethics of scientific, legal, and economic frameworks that embrace nature’s limits and a long-run commitment to the common good, should be at center of the discussions taking shape in the south of Costa Rica, including through the GIZ-Del Monte alliance, but aren’t. In significant ways, the fact that GIZ is supporting the company’s goal of reforesting and regenerating the upper basin while deflecting urgent conversations about the viability of pineapple (and cattle and sugar cane) amount to ratifying its role as an important, perhaps the dominant actor in one of Costa Rica’s largest, most contentious, and economically poorest basins. This ratification is also ultimately psychologically damaging, in ways, because it in effect makes it even harder to ask difficult, obvious questions; to make important connections – between a culture, for example, of pineapple, ranching and sugar cane, and increasing criminality; 3to shape dialogue about and rally support for rapidly transitioning from an export economy back to one based on small-scale farming and fishing, at heart of Costa Rica’s democracy.

The question is, why is the German government supporting this initiative, with its limited focus on reforesting and regenerating selected areas of a contentious region, without placing it in a necessary broader context about the durability of rivers’ flow and health-- in keeping with best practices in Integrated Water Resources Management? IWRM, increasingly based in the science of environmental flows, aims to ensure the long-term health of rivers and other bodies of water, including the amount and timing of water extracted from them. Given the omission of key tenets of IWRM, why is this initiative marketed as a global model?

Ironically perhaps, nor does this model make business sense. Del Monte depends on living rivers to sustain production. But the rivers it depends on, local aquifers it affects, and the Térraba-Sierpe Wetland downstream, are being destroyed in part by the amount and timing of water that the company extracts, and by its sedimentation and agrochemical contamination (together with ranchers’ and sugar cane growers’ use of water and soil). Overextraction of and harm to rivers and aquifers prompted, in part, the company to form the alliance with GIZ—along with wanting to take the lead in securing a new generation of sustainability seals, focused on water security and protecting damaged basins.4 Any plan, however, that does not immediately question the company’s massive concessions, and overall effects on rivers and aquifers, will not be able to guarantee water security for anyone, including the company, most likely even in the short run.

References

León Alfaro, Y., González Brenes, F., & López Estébanez, N. (2022). Fuerzas centrífugas y centrípetas en el Pacífico Sur de Costa Rica: los impactos de la expansión agroindustrial. Investigaciones Geográficas, (77), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.14198/INGEO.18875

Beita, O., & Kiser, M. (2022, September 20). Alianza giz - del monte: una solución falsa para mitigar el deterioro progresivo de la sub-cuenca del rio Volcán. Semanario Universidad.

https://semanariouniversidad.com/opinion/una-solucion-falsa-para-mitigar-el-deterioro-progresivo-de la-subcuenca-del-rio-volcan/

Bermúdez, M., & Alfaro, S. (2020, August 21). Informe técnico caracterización preliminar de la subcuenca del rio Volcán. Área Funcional (AF) Cuencas Hidrográficas, UEN Gestión Ambiental, Servicio Nacional de Acueductos y Alcantarillados (AyA).

Beita, O., & Kiser, M. (2023, March 16). Piña del monte zeroTM: “con un dedo no se tapa el sol.” Surcos Digital. https://surcosdigital.com/pina-del-monte-zero-con-un-dedo-no-se-tapa-el-sol/

Ríos Vivos, Movimiento. (2022, August 6). Llamado a desafiar la gestión del agua dirigida por las corporaciones y a crear opciones justas. Surcos Digital. https://surcosdigital.com/llamado-a-desafiar-la gestion-del-agua-dirigida-por-las-corporaciones-y-a-crear-opciones-justas/

1https://freshdelmonte.com/news/fresh-del-monte-and-giz-strengthen-partnership-to-further-promote sustainability-in-costa-rica-and-guatemala-with-goal-to-duplicate-in-other-regions/

2 https://www.investigacionesgeograficas.com/article/view/18875

3 https://mdpi-res.com/d_attachment/land/land-11-00447/article_deploy/land-11-00447- v2.pdf?version=1647931195

4 https://www.ucr.ac.cr/noticias/2017/05/15/ucr-advirtio-presencia-de-plaguicida-usado-en-pina-en-humedal terraba-sierpe.html; https://youtu.be/wHIdnDglrDg (Additional letters, interviews, photos and notes gathered over 25 years are also available); https://feconcr.com/agua/ganadora-del-premio-del-agua-de-estocolmo-2019- fue-nominada-desde-costa-rica/ (In 2006 national and international water experts toured the south of Costa Rica and organized fora about water sustainability in this region of the country. Building on the momentum of this visit some of the same organizations participated in the nomination of the 2019 winner of the Stockholm water prize).